Selected Articles: Variants

The Fink Variant Rule

by Howard Mahler

from Diplomacy World #4

By adding this rule to regular Diplomacy, one gets an interesting and unusual variant. As for those curious cats out there, the name Fink Rule refers to an abandoned variant on the Mob in New York City in which the idea was that a criminal could turn State's evidence. So now, brought back singlehandedly from deepest, darkest Brooklyn, we present for your amusement and perusement, the Fink Rule.

Each spring the Fink may send in an order such as "I fink on Ionian Sea," but only one such order per spring. If after the spring moves, excluding retreats, a unit of the "right victim country" (the victim country is chosen when you become a Fink) is in the correct space, then that unit is dislodged. The Fink, rather than the owner of the unit, may now choose among the legal retreats, other than off the board, If the unit has no legal retreats, then it is eliminated.

Please notice that when I refer to the correct "space" I mean "each province or body of water" as defined in the 1971 Rule Book. Thus, one could fink on Spain without specifying North or South Coast. If a unit was forced to retreat by a military action that spring, then it may not be successfully finked on. A Fink may not repeat a finking order which was successful (caused a unit to be dislodged) for him at any time in the past. Naturally, if a Fink should be eliminated (owns no more supply centers), then he loses his right to fink. Optional Rule: Even after losing all his supply centers, a Fink continues in the game with full finking powers. In other words, a "phantom fink" can come back from the grave to haunt you.

Being a Fink is like being the President's friend--they each have their disadvantages. First and foremost, the Fink may never build any units. This includes the winter he becomes a Fink. However, since he may try to become a Fink and fail, he may send in build orders that winter. These will only be executed if he fails to become a Fink. (See below on how to become a Fink.) Secondly, the Fink's units may not successfully receive support from another player's units. However, since the Gamesmaster is supposed to try to keep the Fink's identity a secret, he will only reveal that such a support was unsuccessful (for example, by /ngf/ = no good fink) if said support affects the adjudication.

How does one achieve the honor of being shunned and reviled by your fellow rulers? During any winter season, a player may give the order "I want to turn Fink against ______ ," where the blank is filled in with the name of the country. The Fink will only be allowed to fink on this country's units. If there's no Fink at that time and the player is the only one to ask to become the Fink, then he does so. If the former Fink is eliminated one winter, then a player can become the new Fink that same winter. If, by some outbreak of mass insanity, more than one player wants to become a Fink, the one with the fewest supply centers gets the honor. Ties are broken by a random method.

When someone becomes a Fink, the GM will not reveal who the Fink is but will only announce that there is a new Fink. Naturally, he'll inform the new Fink of his new status. The Gamesmaster will only reveal a finking order when it's successful, and this is the first you'll know about which country has been turned fink against. The GM will also announce when a Fink is eliminated during the winter. He will not say who the Fink was, so if more than one player is eliminated in the same winter, you may never know. So in general, you can't be certain of the identity of the Fink, unless he's eliminated or a military situation is affected by the Fink's inability to successfully receive support from another player's units. If you abandon the secrecy concerning the Fink's identity, the finking rule can be used without a Gamesmaster.

Just as it's the rich and the poor who pay no income taxes, so they are the ones who may want to turn Fink. First, there's the player whose country is so shrunken in size that all the player wants is survival and/or revenge. Secondly, there's the powerful player, for example, with 13 or more units and driving for a win, who is strong enough to forsake the privilege of building units. He may turn Fink either to prevent others from doing so at a later date or for the tactical advantage the finking order brings. To say the least, the finking order can be pretty useful in breaking a stalemate line. By the way, there's nothing to stop a Fink from winning since the object is to control 18 supply centers and not to have any fixed number of units.

In the modern world, smaller countries are constrained by the big powers, who in turn are constrained by the threat of nuclear war. Thus, we get the modern concept of limited wars. Similarly, with the Fink Rule, there may be consequences of trying to eliminate a country or of otherwise going too far. Since a player can threaten to become a Fink against a certain country, the finking order adds a new weapon and thus a new dimension to the diplomatic negotiations. Finally, the Fink Rule heightens the chance of enjoying the sweet taste of revenge. In other words, it's fun and after all, that's the whole point of playing the game.

Variant Design

by Lewis Pulsipher

from Diplomacy World #19

(Transcribed by Marvelous Melinda Holley)

A DIALOGUE ABOUT VARIANT DESIGN

((between Ken St. Andrew and myself. In a series of letters we have been disagreeing about this subject since I encountered Peters' HYBORIAN and St. Andre's BARSOOMIAN variants and made various remarks, ending with the first part of the dialogue below. Our comments are naturally somewhat unpolished since we just wrote as things came to mind. The date and initials of the writer precede each set of comments, and much extraneous material has been edited out.))

Pulsipher (LP) (May): It's nice that you guys in Phoenix have become variant fans, but if you don't go about producing variants efficiently you can do more harm than good. Sloppiness and poor play balance are the bane of variant fandom, but that's what we appear to be getting from you guys. I hope it's a false impression.

St. Andre (KSA) (June 1): Neither you nor von Metzke has played HYBORIAN (Peters' variant). I have. Several times. In face to face play the game is generally called between the 10th and 20th moves and awarded to the player with the plurality of supply centers. It is not uncommon for there to be 6 players left in the game at that time with a separation of no more than 5 supply centers/armies between the first place and sixth place players. As for which player wins, it seems to be pretty much up in the air; it is very much a matter of diplomacy, because even the strongest country can be knocked out when two or three of its neighbors decide to do it in.

My limited experience with variants is that no matter how thorough the rules are, you always wind up having to explain something to somebody. Rules for all my variants assume (1) that the players already have some idea of how to play Diplomacy, and (2) that players will use some of their own imagination, look at the map, and try to follow the reasoning that led to the questionable rule...

Here comes a statement you will undoubtedly deplore, but it represents my attitude toward Diplomacy gaming. The Dip establishment has, in my opinion, become something of a nit-picking press (noun form of prissy via back formation). Compiling total statistics on every regular and variant game played through the mails. The object here is enjoyment and the flight of imagination, not statistics. Rigor is less desirable than speed in transforming an idea into reality. If everyone reads your rules, looks at your map, and refuses to play, the variant will die an early death; thus the sport is self-regulating.

LP (June 8): Barring perhaps some of the Tolkien variants, any Dipvar offers reasonably balanced play WHEN THE PLAYERS KNOW THE GAME AND ARE GOOD PLAYERS. No doubt when you lot play Peters' game it comes out all right. But people who see it in DW or anywhere outside your little group won't be aware of the problems, and for that matter many of them will be inexperienced in all Diplomacy play. In that situation, the situation which counts, the balance is bad. Von Metzke or I can see it right off, but we've played the game by mail at least 8 years, and even we couldn't say exactly which countries have the advantage in each situation. Most players are much worse off.

I believe Dipvars can be written with sufficient clarity that only those who are going to be confused by ANY set of rules will have major questions. A problem with Dipvar rules is that people aren’t always reasonable when a problem arises in the course of a game for which there is no referee. Too many are conditioned by the rules to try anything, no matter how underhanded, in order to win. You can't have a reasonable discussion of rules in an atmosphere founded on that attitude.

I've seen too many people and groups go through the hobby with your attitude, to fade away and leave no legacy except a poor reputation for Dipvars. I'm not very keen on stats and so on personally. I'm one of the few people who don't think it would be a disaster if the Boardman Number system and ratings disappeared - but I would like to see standards improved, not remain in the same old slapdash flash-in-the-pan rut. Rigor is far more desirable than speed; there are dozens if not hundreds of speedily produced junkheap variants, so why take a chance on adding to the pile?

KSA (June 22): First of all, I have no sympathy for beginning DIP players who might get in over their heads. It is a great way to learn to swim. Second, by the time a person has enough interest in Dip to subscribe to or even read DW, they should be well past the fumbling amateur stage in their development as a player. Third, in any Dipvariant that makes an attempt to design a game around some well-known fantasy world, a certain amount of imbalance is forced upon the designer by the author's original choice of geography and power alignments. In HYBORIAN Aquilonia, Turna, Nemedia, Vendya and Stygia have to be strong powers because that is the way Howard created them. Peters read and reread the whole Conan saga while designing his game and specifically tailored things to be as faithful as possible to the spirit of the stories while still leaving Conan out of things.

Fourth, the optional gamesmaster units have never been used, so all objections to their hypothetical part in play of the game are merely a wasting of breath. Fifth, the backstabbing nature of the original Dip rules is such that any game based on them is bound to engender at least temporary hard feelings when a person gets knifed. Players definitely should be able to do anything that is legal (or even logical) under the rules in order to win, and if one person sees an advantageous loophole at one time, it will not be long before everyone in the game knows about it. In any case, play-by-mail variants, such as Barsoomian, Kregen, Hyborian, whatever, all have an impartial arbiter as their very foundation, thus questions of rule interpretation are all handled by one man. Players retain their freedom of choice: either go along with the interpretation of the GM or quit and try to find someone else who will treat them better. A GM who angers all of his players soon won't have any, and will automatically cease to be of any importance.

Sixth, when you mix decidedly weaker-layer countries with stronger-player countries, it forces more real diplomacy to surface, as the only way the little guys can hope to win is by teaming against the big guys. For all of these reasons I maintain that Peters' game is as good, exciting, and interesting a variant as any around.

LP (late June/early July, and somewhat curt because I ran out of space on the aerogramme!): First: most variant players are beginners so far as variants are concerned. They usually drown rather than learn to swim if immediately thrown into quicksand. Second, most DW subbers are rank beginners - where do you think the recent doubling of circulation has come from? Third, designing a variant around a fantasy world is no more difficult - less difficult because there's less information than designing a historical variant. So much fudging is necessary to adapt the peculiar game system that one may as well make the thing balanced on the way. Fourth, optional rules are printed to be played, so objections are quite germane whether they've actually been played before or not. Fifth, most people disagree with your view of "anything is fair" in Diplomacy, believe it or not. Sixth, postal-only variants are a dying breed, and GMs aren't often available for face-to-face. I'll never put a postal-only variant in DW unless it takes very little room. GMs virtually never get such bad reputations that they can't find players - there is only one example of this excluding those who actually quit outright.

KSA (July 12): One of my basic feels about game design is that life isn't fair, and that games shouldn't be either. I'm very competitive, and the idea of winning against odds is more attractive to me than merely winning a fair fight. In a case of big guys and little guys I could upon the natural intelligence of my players to figure out what they will have to do to even things out or give themselves a chance. And I also make myself available to anyone who will take the trouble to simply ask me about anything that bothers them. I will not reveal what other players are doing, but I'm glad to share any strategic knowledge about the game that might help them make a better move than a beginner might ordinarily make.

I also try to show people who correspond with me that I don't consider myself infallible or my rules perfect. Things need to be tried out. If I make a mistake, I'll know better next time, and meanwhile let's correct it and forget it, and either get on with the game or forget the whole thing.

With so many major issues, crimes, hoaxes, shoddy merchandise, etc., in the world, I don't believe that getting stuck in a Diplomacy variant that you don't enjoy is that big a deal. If you don't like the game, quit. I don't believe that I have any responsibility at all to the rest of the Diplomacy-playing world - I'm doing this game design and magazine publishing for my own enjoyment and at my own expense. I have a personal responsibility to my players to try and make their gaming enjoyable, and I do my best, but that is all.

One thing I am against is standardization; the thought of everyone playing nothing but the original European 1901 game of Diplomacy is enough to make me puke. At GLASC-II convention, it was a real bummer not to be able to gather a mere 6 players or so to try one fantasy variant, especially when I brought five along, but that's their prerogative.

This letter has gotten pretty far afield - I guess I just can't accept your hostile attitude regarding outlooks on Dipdom.

LP (19-20 July): I never thought it is a justification for lousy work to say that other people do lousy work, nor do I think it a justification for poor variants to say that many other things in the world are poor, unfair, etc. If you can't make the variant good enough that people won't quit because of poor construction, regardless of the merit of the ideas, you shouldn't be doing it in the first place. I guess this presents a perfectionist's as against your - what shall I call it? - impatient young man's view. Even idealist's view? I don't know.

Or it may be that I'm the idealist, you the cynic. I would like to see standards raised so that fewer people will waste their time or be put off by a lousy first experience. You seem to regard it as part of the game, and devil take the hindmost. Is this a fair statement? Then again, you are idealistic in your view that people OUGHT to like variants. Whether they ought to or not, they often don't give two hoots for them. Your experience at GLASC-II was not at all uncommon. People don't often like variants, Ken, and the ONLY way to get more people to like variants is to raise the standard of variant design. The most frequently heard objection to variants in this country ((U.K.)) is that none is as good a game as standard Dip. You know that's not true, and I know it, but too many people learn about variants via some junkheap someone threw together, and they assume all variants are the same kind of junk. Yes, I'm downright hostile to junk variants, because I've seen that it does to variant fandom when people encounter the things.

Oh, yes. I agree life isn't fair. Isn't that a good reason for making games fair, since games are a form of escape from life? You can say all you want about mental competition and so on, but in the end games are escape, whatever else they may be.

Counting upon the natural intelligence of your players is all very well IF experience bears out your assumption. It does not. Even in a balanced and familiar game, when a player forges into the lead players as often as not line up to see who will get second place rather than gang up on the leader. (Note the statistics in Berch's article for the country most vulnerable to a gang.) So much for "natural intelligence." You have to remember, Ken, that there is disagreement about the basic objective in Diplomacy. An ASTONISHING number of players prefer second place, what I call a loss, to a draw of any sort, what I call a partial win (at least you haven't lost). I suspect you don't play for second, nor do I, but a great many players Do, and you must take that into account when you design a variant. You simply cannot assume everyone plays the same way you or your group do.

((At this point I sent a copy of the article thus far, in case he wanted to add something.))

KSA (Aug. 24): Your long paragraph, where you state that fantasy variants are no more difficult to design than historical variants. I believe I admitted that but also stated that I think they are more interesting, because (1) of the local color and excitement imported to a particular world, and (2) because of the chance to try out radically innovative rules to conform to some special practice in the author's writing.

I would like to put in a comment on our different basic attitudes. You take a protective, paternalistic view which assumes that most gamers don't want to and shouldn't have to use their brains or imagination to understand anything. I, on the contrary, assume the best of players; that is, they WILL know what they are doing, and if they don't know, then they deserve to be beaten by players who do know. My whole attitude is Caveat Diplomator. Laissez-faire rather than paternalism.

LP (Oct. 10): In your letter is a perfect example of some of the things I've been talking about. I told you your Aztlan Rule 3.2 ((about armies and their relationship to economic spaces)) wasn't clear. You say I should reread it and see introduction where it clearly stated that Aztlan is a blitz variant, which means multiples armies and interesting rules. But I HAD seen the introduction, and as a very experienced variants rule-reader I went over 3.2 quite carefully before I wrote you. You can't expect people to know what you mean by "blitz variant," YET YOU DON'T EXPLAIN WHAT YOU MEAN IN THE RULES! Even if, in the rules, you had included the latter part of the sentence you wrote to me, you wouldn't have clarified it. "Interesting rules" can mean anything, and I can name a dozen variants with multiples armies of one sort of another, not one of which regularly permits one economic location to support more than one unit (which Aztlan does, so to speak) - in fact, most of them maintain a one-to-one relationship between each unit of strength and each center, even though more than one unit of strength may occupy the same space. You can't expect people to read your mind - your ignorance of others who use the same idea (multiple armies) which a different economic base doesn't excuse you. Unlike the character in Alice in Wonderland, you can't make words mean anything you want them to.

We haven't been on the same wavelength. You speak of what you would like to think gamers are like. I haven't said anything about what I wish they were like, I only speak of what they ARE like. Wishful thinking won't make people conform to one's ideas - to ASSUME the best of players doesn't make your assumption true. Your assumption merely means, in practice, that those more adept at guessing, or with minds more like yours, or who have better access to your interpretations, have an advantage over those who don't. My attitude is not paternalistic, it is realistic. Everywhere one looks in gaming, especially "behind the scenes" as I've been able to observe here through Games & Puzzles and Games Workshop, the FACT that gamers don't read carefully and are easily confused becomes more and more obvious. At times it becomes quite incredible, but that's the way it is. Diplomacy players are no different from any other kind of strategic game players in this respect.

Variant Design

by Lewis Pulsipher

From Diplomacy World #20

Transcribed by Marvelous Melinda Holley

It seems that an international Diplomacy activity of any sort is hard to organize successfully. The first Variant Design Competition suffered because only North Americans entered. Having moved across the water, I tried again from the European side; this time there were entries from the Netherlands, Belgium (including one Pole), Denmark/Switzerland (but he is English), Northern Ireland and Canada – but not from the USA or the island of Great Britain! There were no entries in the SF/F category. John Lipscomb of Canada won in the historical category with his ANCIENT EMPIRES II (no relation to John Boyer’s game). Nicky Palmer of England won the simple variant category with his entries printed here. Michael Liesnard won the open category with his QUEST FOR THE RUNIC CHIP, which will appear here next issue. (Note: I have had trouble distributing the prizes because I’ve lost contact with Nicky Palmer. Anybody know where he is?)

Thanks to all who entered or contributed prizes.

PACIFIST DIPLOMACY

by Nicky Palmer

- Rules as standard DIPLOMACY except where stated.

- In every year in which a player neither gains a center from, or loses one to, another player, an intra unit can be built in any home center. Such units are referred to as “bonus units” and are marked with an asterisk, e.g. F* Kie-Hol. Bonus units reflect extra economic strength for powers not interested in major territorial changes.

- In every year in which the condition in Rule 2 is not satisfied, the player loses one bonus unit (his choice). When all bonus units have been lost this has no effect – losses are not saved up, and a “year of peace” will again generate a bonus unit.

- Bonus units are built and removed in Winter. Removals cannot replace or be replaced by regular removals – the two types of unit are accounted for separately. Bonus builds can be saved up.

- Victory is by overall majority of centers, not units.

COMMENT: The purpose of this variant is to add a new alternative strategy: holding back (except for neutral conquest) and building up forces for a big offensive later. Not, perhaps, pure pacifism! – but an intriguing alternative to non-stop attack. Secondary virtue: gives hope to 1- and 2-unit powers who may have a better chance of avoiding center changes than the “superpowers”.

SHADOW WORLDS

by Nicky Palmer

- Rules as standard DIPLOMACY except where stated.

- Each player has the same country in two simultaneous games, “A” and “B”.

- Before the Winter adjustments in the simultaneous games, each player lists the centers he owns in either game, counting his home centers only double if owned in both games; all non-home centers only count once even if held in both games. Thus if Italy owns: (A) Ven, Rom, Nap, Tri, Mar; (B) Ven, Tri, Nap, Vie, Tun, he is counted as holding 9 centers: 2x (Tri, Nap) + Rom, Tun, Mar, Tri, Vie – not 10 as it would be if Tri were counted twice.

- These centers may be divided each year between the two games as the player wishes; in the example, if Italy had 6 units in “A” and 2 in “B”, he could build 1 in either game – or disband a unit in one game and build two in the other, or cut his losses and go down to zero in “B” and build three in “A”. (Note that this would not preclude his rebuilding in “B” in a later year, if his build centers had not yet been captured.) Play continues on both boards until one player has all 34 centers in his control list (not necessarily all on the same board). If two achieve this simultaneously, the result is a draw. For a shorter game, substitute 18 for 34.

COMMENT: The fastest growth is achieved by stabbing in opposite directions in the “shadow worlds” – but this risks alienating one’s allies in each! Added to this tricky strategic problem are various tactical twists: when to strip one board to the benefit of the other, and the balanced growth vs. alternating drives on each board. Note that one can win even if wiped out on one board – but only just, by completely conquering the other.

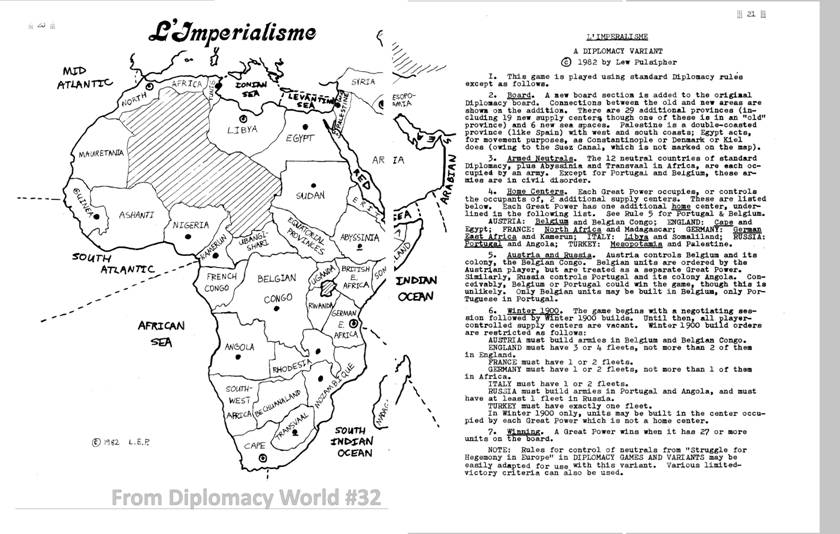

L'Imperialisme by Lewis Pulsipher

From Diplomacy World #32

Strategic Concepts of Colonia

By Jack McHugh

From Diplomacy World #62

Colonia, while using the mechanics of Diplomacy, is a somewhat different game in strategy from Dip. Colonia puts more emphasis on the grand strategic view than its parent game, and leads to more stress on alliance play.

A game of Diplomacy begins with the players' objectives dictated, to a large extent, by the board. That is to say, Austria will attempt to be Balkan power, England a naval power in Scandinavia and northern Europe, Italy a Mediterranean power, etc. It is difficult, and in some cases impossible, for the players to significantly alter these enforced stratagems.

Not so in Colonia. Although it is true that most players have a home area in Europe, the players can change the nature of their holdings by trading various pieces of real estate around the globe. For example, France could trade Dakar to Portugal in exchange for Alaska, accomplishing a switch of colonial build centers in America and Europe. The result strengthens both powers as they each have concentrated their build centers in one area. This also reduces the possibility of stabs as neither player now would want the other's centers on their respective continents.

No longer is one power in the board designated the "naval power" when one plays Colonia. In Diplomacy, England generally builds little but fleets and is alone in doing so. However, in Colonia there are often other powers, such as Portugal or Netherlands, that also may adopt the fleet policy with some measure of success.

What Colonia asks of its players is strategic imagination and flexibility. It is possible for a player to completely relocate from Europe to his colonial holdings. A power could, for example, gain control of all the build centers in North America by trading his European holdings for help in America. This would give that power four new build centers in America, which is more than anyone (except Russia) starts out with in Europe.

Those are my opening remarks. Now I would like to enunciate some strategic rules that future Colonia players may find useful.

Rule 1: Play Game Long Alliances

Since there are so many units, it is almost impossible to win solo in this game. Given that fact, why not have an ally or two right from the beginning and increase your chances of winning?

Rule 2: Don't Hesitate to Concentrate Strength

As I said earlier, it is possible to do some horse trading early and thereby concentrate your holdings. This will strengthen your hand and discourage stabs. Decide where you want to be a major power and don't be afraid to trade away or lose the rest.

Rule 3: Control the Choke Points

On the Colonia VI board, there are a number of choke points, the control of which is imperative for a successful strategy. Geography should influence your tactics in this regard, though not as much as it would in regular Dip. If you are playing Austria and decide on a Pacific strategy, you should count on keeping both Polynesia and the Central Pacific Ocean clear of foreign units after the first few turns.

Rule 4: Draft Orders Carefully

Because Colonia involves a large number of units, you will need to spend a lot of time both in planning and actually writing your moves. I find it necessary to number my units so as not to overlook any of them. You will also need time to check out where other countries' units are and where said units can move to.

Rule 5: Develop an Overall Growth Plan

The first two years of any Colonia game are spent with all powers gobbling up neutral centers that surround them. This early period is ideal for talking to other players and deciding exactly where builds are to be concentrated. If you are playing the Netherlands, this is the time to decide to cut a deal with the Turks about Goo or to talk to Austria about trading your help into Poland for their help in the Pacific.

Rule 6: Be Open to Other Offers

Although I have emphasized the importance of making your own plans, sometimes an uncooperative neighbor will make those plans difficult to execute. There are more players in Colonia than Diplomacy, so if someone wants to work with you don't be afraid to radically alter your plans to make such an alliance practicable. In fact, it may be better to plan to grow in more than one area. Down the road you can decide which area to concentrate on based upon least resistance and/or most cooperative allies.

Rule 7: Write Early and Often

The most critical part of any game, whether it be Diplomacy or a variant, is early in the game. Even if you can't follow up your first letters within a turn or two, it is crucial to write everyone the first turn. This is even more true in Colonia, as many powers who are not European neighbors may be close to one another overseas.

I can scarcely overemphasize this latter point. Once players hear nothing from you while other powers are in contact with them, they are less likely to change their plans later even if you become a more reliable communicator. And, of course, don't think that other players aren't busy telling everyone what a louse you are and how you never write in any game you are in… and how you should be killed here in this game, immediately, for this breach of Diplomacy etiquette.

Provincial Diplomacy

By Jef Bryant

Originally published in Diplomacy World #74

All the rules of classic Diplomacy apply except for the modifications below.

1. No Supply Centers

There are no supply centers.

2. Build Centers

What used to be the national supply centers are now build centers.

3. Occupied Provinces

Each occupied province provides 0.5 points at the end of every Autumn (Fall) season.

4. Unit Maintenance or Build

A unit can be maintained or built by using 1 point per unit.

5. Additional Provinces

Additional home provinces are provided for Russia who owns the Caspian mud flats and Turkey who owns Cyprus at the start of the game to equilibrate the provinces for each power.

6. Game Start

The game starts like the Winter 1900 variant. Players send in a choice of a fleet or army for coastal build centers along with their Spring 1901 orders.

7. Copyright Notice

This variant is (c) February 1993 by Jef Bryant. Copies can be distributed freely for postal play and variant banks. Any modification of this variant is prohibited without permission of the designer.

8. Extra Terrestrial Provinces

With the extra terrestrial provinces: Ireland (Ire), Iceland (Ice), Sardinia (Sar), Corsica (Cor), Sicily (Sic), Cyprus (Cyp), Crete (Cre) and the Caspian mud flats (Cas) there are now 64 terrestrial provinces on the board. The winner of the game is the player who owns 33 provinces after an Autumn (Fall) adjudication.

9. Occupied Provinces Definition

An occupied province is defined as the power who last occupied it during an Autumn (Fall) season. Each power owns his home provinces at the start of the game.

10. Point Distribution

Any points or half-points not used cannot be kept and are lost after each Winter build season. However, in order to encourage communication between the players, points (including half-points) may be traded or simply given to other players.

Is it Thanksgiving Again? Turkish Strategy for Colonial Diplomacy

by Thomas Pasko

Last December, TAHGC released Colonial Diplomacy. This game uses similar game mechanics as Diplomacy and depicts an accurate, historical view of the Colonial Period. There are many topics of discussion possible for this game, but I will try to discuss the strategy for the player choosing Turkey.

In 1870, the year the game starts, Turkey has been placed between Russia and Britain. Both of these powers are stronger than Turkey, but both powers also span the length of the mapboard. Because of this DIPLOMACY is very important, especially at the start of the game. He should talk to both China & Japan and to Holland & France. If these countries are willing to attack his neighbors from the East, he doesn't have to be so timid during the diplomacy stages.

Because of the great dependence on diplomacy and the actions of others, some people have come up with an opening coined, "The Camp David Opening". The main goal for this opening is to keep peace in the Middle East, as well as give everyone involved the chance to collect neutral supply centers.

The Camp David Opening:

1870 Russia: F Ode-BS, A Mos-Bok Turkey: F Con-Med, A Ang-Arm, F Bag-PG England: F Aden-RS 1872 Russia: F BS-Rum, A Bok-Per Turkey: F Med-Egy, A Arm-Tab, F PG-Shi England: F RS-Sud

The idea behind this is that it maximizes the builds (six!) and lets all three powers see what develops. A conflict in Egypt costs England & Turkey equally and A Mos-Bak exposes Russian intentions, as well as costing her a build.

This opening should be coined, "The Ostrich Maneuver". It gives you time to grow, but it doesn't look into the future and doesn't give you many options after the first two turns are over. You are stuck with either an advance upon Russia and/or Britain. Those are your only two viable options. Sticking your head into the ground in Diplomacy will get you an early seat in front of the television every time.

To create an opening that really works Turkey has to work with one goal in mind, to obtain the rights to Persia because, Persia is the key to the East. Persia must be held for Turkey to be able to march his armies to the Eastern territories. He would march thru Afghanistan, right above Britain [Karachi & India] and below Russia [Boku & Tashkent].

If Turkey is not allowed to own Persia, he is forced to attack one of his neighbors. Why? Because he can't get to anyone else!

Turkey's first business should be to find out what plans the countries in the East have. This shouldn't be too hard, because the Far East will not view him as an enemy. If France & Holland have teamed together, Turkey can count on his southern route possibly being quite soft in a few years. If Britain isn't attacked by a united front any bargaining chip that Turkey has at the start, even if it is a small one, disappears. Britain has a possible "6" builds from the start and if he's working with France and/or Holland, he'll probably get them.

The biggest variable with deciding Turkish strategy, is the Russian player. The mapboard has enough supply centers in the West that I've seen Russia retreat from the Eastern Sea-board, hit the West hard, and then reclaim the East. If Russia is going to be attacked in the East, then the bargaining chip that Turkey has against him has to be used. Claim Persia, offer Rumania in exchange. State Bak "DMZ". This will alleviate the bottleneck, and give you room to grow. Russia, shouldn't mind giving up Persia, since he will be able to concentrate his forces in the East. Don't be fooled to see his armies go East, they could be in your lap before you know it. The Trans-Siberian Railroad is the main reason why Russia & Turkey don't normally function well together. Turkey knows that Russia can be at her door at any moment & Russia knows it too. It's a loaded gun and someone's always going to try and pull that trigger first.

Initially, it's not in Turkey's best interests to strike out at anybody, unless Russia is sitting in Bak. Even then, whine, bitch, & moan. Maybe you'll get some form of reaction. Nothing Britain does in the first couple of turns, could make it beneficial for you to strike him.

There are two variations to the Camp David Opening.

Number 1 - The Camp David Sea Maneuver:

1870 Russia: F Ode H, A Mos-Bok Turkey: F Con-Med, A Ang-Arm, F Bag-PG England: F Aden-RS, F Bom-Ara.S 1872 Russia: F Ode-Rum, A Bok-Tas Turkey: F Med-Egy, A Arm-Tab, F PG-Per England: F RS-Sud, F Ara.S-Kar

Number 2 - The Camp David Land Maneuver:

1870 Russia: F Ode H, A Mos-Bok Turkey: F Con-Med, A Ang-Arm, F Bag-PG England: F Aden-RS, F Bom-Ara.S 1872 Russia: F Ode-Rum, A Bok-Tas Turkey: F Med-Egy, A Arm-Tab, F PG-Shi England: F Ara.S-Kar, F RS-Sud 1874 Turkey: A Tab-Per

For either of these openings, Turkey will have to work with his neighbors. If he chooses the Sea option, then all he has to worry about is Russia bouncing him out of Persia. If the Land option is chosen, then he can use either one of his neighbors to support his 1874 move if the need arises.

Both of these options will benefit Turkey's neighbors, actually each one benefits his neighbors in different ways. The main objective of this opening is for Turkey to be able to move his forces out into the board and still keep peaceful relations with his neighbors.

Since these Camp David openings help relieve the pressure that can occur between Russia & Britain and Turkey, it's easy to see if any neighbors are interested in an initial conquest of Turkey's territories. Any neighbor that won't discuss these options, definitely has something up his sleeve.

The Camp David Openings, whether by Sea or by Land, is a formidable opening for the player drawing Turkey and is a foundation for lasting relationships with his neighbors.

Thomas Pasko publishes the Dip zine CDD Medical Journal, which is regarded as the main base of PBM Colonial Diplomacy.

The Problem With Fantasy Variants

by Stephen Agar

The basic ingredients of any Diplomacy variant is a scenario where several (usually at least five, preferably seven) more or less equal Powers take part in a conflict for domination of a geographical area. The geographical scale of this conflict is not of itself important, it could be a city (as in Mobtown), a country (as in War of the Roses), a continent (as in Abstraction), the planet (as in Mercator), the solar system (as in Apposition), and so on. Now this approach is fine for historical variants, the budding designer merely confines himself to those periods of conflict where a number of competing factions have been battling it out, and ignores human conflict which is essentially just two-sided (e.g. the Hundred Years War, English Civil War, American Civil War, Franco-Prussian War etc.). After all as the essence of Diplomacy is the ability to have a changing alliance structure, games where the number of protagonists is small are not going to be very exciting or practical.

There are several difficulties in adapting fantasy novels to this basic formula. First, although there may be a superficial appearance in the novel of a number of Powers battling it out (Elves, Dwarves, Orcs, Ents etc.) all too often the basic story often revolves round the age old Good vs. Evil storyline - a two-sided fight with restricted scope for diplomacy. Second, in fantasy novels the impact of individuals is often out of all proportion to their numbers - the effect that a Conan, an Elric or a Gandalf may have on a campaign may be far more important than the weight of numbers behind him or against him. Third fantasy novels are, in the end, novels. They are telling a story. While it is possible to place a Diplomacy variant in a fantasy world, if you want the variant to have the flavour of the plot, then you will need to make the rules very complex indeed.

Therefore the variant designer must make one basic choice before he gets very far in his new design - is he just going to use the geography of the fantasy world turning his game into essentially a map change variant (e.g. Young Kingdoms I (Elric) or Middle Earth II (Lord of the Rings)), is he going to tackle the problems posed by the characters and the plot of the novel which will usually involve Personality Units and special locations (e.g. Downfall (LotR) or Black Blade (Elric)) .or is the variant going to be some compromise between the two (e.g. Third Age (LotR) or Age of the Young Kingdoms (Elric)). When I designed my Young Kingdom variants, my initial attraction to the Elric stories was the idea of having a map which consisted of land masses clustered around a central sea, because I thought this would provide an ideal vehicle for Fred Davis's A/F rules. In Young Kingdoms II I endeavoured to improve the map balance, add a device for breaking stalemate lines and then threw Elric in for good measure.

One inevitable problem in trying to introduce characters from the book is that the ratio of Heroes to Powers is invariably not 1:1. Some Powers will have no Heroes or Personality Units, other will have several. Therefore you must either find counterbalancing Personality Units for the Powers without them (which involves stretching the original story), hive off some of the Heroes/Personalities to additional players (which can make the variant need so many players as to become difficult to get off the ground or introduce players with a lessened degree of involvement in the game), or just accept that the game cannot be equally balanced in terms of manpower.

A surprising number of the plots in fantasy novels also revolve around unequal conflicts - i.e. the forces of Evil are large and powerful, sweep all in front of them, but are ultimately defeated not by the armies of Good but by the Hero. This tends to mean that the Evil player(s) start off very strong (hence Mordor’s 2A’s in Downfall) which can make the game very imbalanced, or the Personality Units end up dominating the game. The designer then has to come up with some restrictions on alliances in the game to stop the Orcs teaming up with the Elves and the Ents to crush the Gondor/Mordor alliance, because such an alliance structure would be contrary to the mythical historical premise on which the game is based. It should be noted that fanciful alliance structures are not necessarily thought to be a problem in regular Diplomacy.

When you consider all the chrome which has been added to the various versions of Downfall of the Lord of the Rings (Personality Units, the Ring, Special Locations, Multiple Units, Cavalry Units, Special Rules etc.) you can perhaps understand why it has been through 20-odd revisions. Some versions seek to make the variant more like the book, some seek to make the variant more playable, and (I suspect) never the two shall meet.

Are these variants worth playing? Well, it depends. If you want to try out Diplomacy in a fantasy scenario then of course they’re worth playing, but don’t expect the game to be anything like as balanced as a regular game. On the other hand, if you want to relive the tribulations of Frodo as he seeks to destroy the power of Sauron then either turn to computer games or better still re-read the book. All in all, fantasy novels do not make good subjects for balanced Diplomacy variants.

Stephen Agar is obviously quite a fan of variant play and design.

Japan - The Land of Opportunity: A Look at Opening Strategies for Colonial Diplomacy

by Mike Oliveri

There are many ways to play Diplomacy and its new variant Colonial Diplomacy. Heavy tactics, heavy strategy, heavy dipping and any combination of the three. But, if you find that your game tends to go towards Heavy Strategy, have I got a country for you!

Each country in Colonial Diplomacy starts with very different positions, and, therefore, very different immediate concerns. They are not all the same size. They do not have the same opportunity for growth. Many are immediately thrust into a hot bed of controversy. But unlike any of the other nations, Japan can actually think about what its game plan is going to be. Japan starts with 4 centers with nothing but beautiful water all around. No one can get to her without a concerted effort, and every attempt to do so is telegraphed well in advance. So sit back. Put up your feet. Relax. You've got time to think about what you want to do. And as the world becomes smaller with each passing turn, you have time to change your mind.

An overstatement for sure, but not far from the truth. Japan starts as a middle power with 3 fleets and 1 army. Three countries have more units than her. Three have fewer. But she doesn't have to worry about the entire board, as Britain and Russia do. And she is not land locked, as China is, so the extra unit can be used any way that she chooses. As Japan, your main decision is going to be do you get involved in the battle for Seoul and Fusan, or do you send your fleets south to get the lion's share of open centers in Formosa, Manila, Cebu, and Davao. It is not an easy decision. You will more than likely want to do both. So let's look at each option individually. Then we can mix and match, and hopefully come up with a strong opening.

The Philippine Opening

"I've talked to everyone. Russia and China are going to be at each other's throats. Holland is worried about Britain, and France doesn't have a clue. It's everything I could have hoped for!" If you ever start the 1870 turn with these thoughts, this opening could give you a giant step on all the other players. The key, of course, is Russia and China. If they are going to be fighting to the death, you can swoop south and pick up two centers before anyone knows what is going on. I want to call this a "closed door" opening, because your views towards Russia and China are at best neutral, and your initial involvement will be totally nil.

1870 - F Ota-Os; F Kyu-Ecs; F Tok-Up; A Kyo-Kyu 1872 - F Os-Sak; F Esc C A Kyu-For; A Kyu-For; F Up-Mp

Sak may be red on the map, but it belongs to Japan. No matter what opening you choose, something has to go to Os in 1870 and Sak in 1872. If you find that For is being challenged, try to talk your way through taking it without a support. (This is diplomacy, after all.) But if you cannot take the chance, support the convoy from Up. The important thing is to get the two builds. Your second goal is to slip as far as you can into the Pacific spaces. Build? Two fleets, Kyu and Kyo.

1874 - F Mp C A For-Cebu; A For-Cebu; F Ecs-For; F Kyu-Ecs; F Kyo-Up; F Sak-Os

At first glance, you may think I am being whimsical with my suggested moves for 1874, but I am not. Again, I believe that a strategy has to be backed up by diplomacy, and that the strategy has to be flexible enough to adjust to the tone of the diplomacy taking place. For the above moves to work, you need a good relationship with Britain. Only Britain can get to Formosa and Cebu as quickly as you, and then only if Hong Kong is abandoned. If you want Cebu badly enough, you should be able to get it even with a naked convoy.

From this position, you have an excellent chance to take Mna from Mp for two more builds. If you have been lucky enough to not be pulled into the affairs of the mainland, now is the time to open your eyes. You have ignored Russia and China long enough, and you cannot afford to let either of them get the upper hand. Pick one and use the other. And never give up your base in the Philippines.

The Open Door Opening

"I've talked to everyone. Russia and China are going to be at each other's throats. ..." Isn't strategizing wonderful! Everything is the same, it's just that this time around you have this unquenchable desire to convoy, convoy, convoy. Well if that is what you want, let's get to it. Whether you are going to be pro-Chinese or pro-Russian, the opening is the same, and that is the beauty of it. You won't be committed one way or the other until 1874.

1870 - F Ota-Soj; F Kyu-Ys; F Tok-Os; A Kyo H

The F Tok-Os is mandatory, as is A Kyo H. If Ota moves to Soj, something has to move to Os. Don't forget, Sak is yours. Don't miss the only sure build you have. By moving Kyo to Aki, you open only one additional option (F Os C A Aki-Sak, followed by F Os C A Sak-Vla). Although this would probably be fun to play, I think it limits your ability to play the Chinese and the Russians for the best offer, and they will offer.

1872 - F Ys C A Kyo-Fus; F Soj S A Kyo-Fus; A Kyo-Fus; F Os-Sak

At this point, you have gained two centers, and have not moved in anyway against Russia or China. During those two turns, your diplomacy should have generated a number of options. Now you can pick the best one and build accordingly. If you choose to play the pro-Russian variant, you will want to convoy into mainland China, either Sha or Nan. If you choose the pro-Chinese variant, you will want to convoy into Vla and Seo. In fact, the question of Seo possession can be addressed in 1872. I used A Kyo-Fus only because neither Russia nor China should protest your desire to occupy it. But you may be able to get both of them to concede Seo to you in 1872 in return for your support against the other. Remember, right now they both need you. So use it and them to your best advantage.

Unlike the Philippine Opening, where you ignored everything else until 1878, with either Open Door option, you will have to address the south with your builds. Because of this, you may decide to build fleets in 1872 and postpone the army builds until 1876. You have already given up Cebu to either Holland or Britain, and a single fleet may have trouble taking Formosa. So building a second fleet in 1872 can not be ignored. But remember that you have committed to a mainland game. Get Formosa, build a defensive line, and then press your advantage by getting as many armies as you can onto the mainland.

Attacking China will give you more growth opportunities, but attacking Russia may be easier to pull off. If you were able to take Seo instead of Fus, then moving to Fus may buy you more time to make a decision. Stall if you must, but don't be surprised if you begin to be pressured by your want to be allies to get off the fence. In any case, it's still your choice. Go for the gold!

The Open Door Philippine Opening

What is that saying? "Compromise is the spice of life." What ever it is, that is the basis of this opening. "Jeez, I really want Fus, and For, and Sak. And I can't ignore two of the major powers of the game from turn one. And I can't pretend that everyone and his cousin isn't racing for the Philippines. Gawd! What can I do?"

If you can't choose between one of the two openings described above, don't. Heck, your Japan. You really can have it all. Well, at least you can try for it. I have only seen two games of Colonial Diplomacy played, and in both cases Japan has opened with three builds. Now I acknowledge that two games is not a great sample, but it does show that it can be done. And I wouldn't be surprised to find that the only time it fails is when Russia and China decide to work together instead of against each other. That will happen once in a while, but more often than not, they will be at each others throat. The challenge is not can Japan get three builds. The challenge is can your diplomacy keep R/C from forming.

1870 - F Ota-Soj; F Tok-Os; F Kyu-Up; A Kyo-Aki 1872 - F Soj C A Aki-Fus; A Aki-Fus; F Os-Sak; F Up-For

Moving the fleet to Up or Ecs is up to you. I prefer Up only so the option can be investigated of bypassing For and moving instead to Mp. Getting to Cebu first is very important, and you may decide that the delayed build is worth the prize. One thing that every country has to look at in this game is the value of racing to the furthest center and then back filling the bypassed centers in the next few turns. In Diplomacy, the open centers are fewer and closer to one or another of the playing countries. So, this option just isn't available. In fact, if it were attempted, the stranded and unsupported unit would almost always be forced to retreat in the very next cycle of turns. In Colonial Diplomacy, the opposite seems to be true. Because of the number of open centers and their distance from other playing countries, a single unit can take and hold a distant center beyond the first two cycles of turns. This then becomes an important issue of your strategy. Can you stretch your lines or must you play closer to the breast?

The A Kyo-Aki should be considered mandatory. By moving to Aki, you are adding options for 1872. The threat of F Os C A Aki-Vla with support from Soj, is very real. It is important that Ys is not entered by Russia. Also, you will want assurances that you will be allowed to enter Fus. If friendly negotiations cannot bring you to these agreements, then the threat of the other may soften a staunch Russian stance.

So there you have it. Three different openings with options galore even after you have chosen one of them. What more could the strategist in all of us ask for? OK, time to get off your duff and put your plan into action!

Mike Oliveri is a new contributor to Diplomacy World. He's also a card shark.

CDD Lab Notes

by Tom Pasko

Disease: Colonial Diplomatic Developmentitis.

Test Subject: Name withheld. Shall be referred to as TestCase #2.

There have been many symptoms stemming from this new and unknown disease. One of the most prolific is the Railroad Blues, or what we call, "I'm here, He's there, How did he go over there?". This Testcase shows this symptom and it is in an advanced stage.

The Trans-Siberian Railroad, [TSR], adds new dimensions to playing Russia in a Diplomacy game. The TSR stretches through 6 provinces, from Moscow to Perm to Omsk to Krasnoyarsk to Irkutsk to Vladivostok. The Russian player can move one army unit along the TSR per turn. The following rule section has been reprinted from the published rulebook.

9.2 The Trans-Siberian Railroad (TSR)

The TSR runs from Moscow to Vladivostok and allows for rapid mobilization of Russian army units across the vast Russian continent (i.e., it allows army units to move more than one province in a turn). The following rules govern its use.

9.21

This is an additional order which may be used by the Russian player and is designated "TSR" on the order sheet. This designation is placed between the names of the starting and finishing provinces. Thus an army in Moscow intending to move to Irkutsk would have orders " A MOS-TSR-IRK".

9.22

Only one unit may use the TSR per turn.

9.23

A unit using the TSR may only be transported to an unoccupied province. It may not perform any other function that turn (i.e., it may not attack an occupied province or give support to any other province). For example, an army in Moscow wishing to support a unit in Vladivostok or attack an enemy unit there, would have to move to Irkutsk on one move and then support or attack Vladivostok next move.

9.24

A unit may travel as far as it is allowed to go along the TSR according to the normal rules of conflict.

9.241

Thus if any other major power has a military unit in a province along the line of the TSR a Russian unit would have to stop in the nearest empty province along the line of the railroad before the enemy-occupied province. For example, with a Chinese army in Krasnoyarsk, a Russian army starting in Moscow could travel only as far as Omsk.

9.242

However, if two equal forces attack a province on the TSR resulting in a standoff, the TSR order is not disrupted and the Russian order would go ahead. (The same situation as having to dislodge a fleet in order to stop a convoy order.)

9.25

If a foreign power attacks a province on the TSR, to which or through which a Russian unit had been ordered to move, this would result in a standoff and neither unit would enter that province (unless the attacking unit had support). The Russian unit would stop in the nearest empty province along the line of the railroad. Example - RUSSIAN: A MOS-TSR-VLA, CHINA: A MON-KRA.

9.26

A unit using the TSR may receive support to enter an empty province along the line of the TSR, to stop a standoff as occurred in the above example. Example - CHINA: A MAC-IRK, RUSSIAN: A MOS-TSR-IRK, A VLA S A MOS-IRK. The Russian army in Moscow moves to Irkutsk.

9.27

The presence of a Russian army unit on the line of the TSR does not block its path. A unit using the TSR may pass through a province occupied by a Russian unit as long as it doesn't end its movement in that province.

These rules are very well written, but a few situations might need some clarification for some of us. I consulted Dr. Peter Hawes, the creator of the CDD virus. Working in conjunction with his research lab, we have come up with the following added information:

Clarification Information

1: If a foreign power is in control of OMSK, a Russian unit must stop in OMSK.

Clarification Examples:

1: If a foreign power has a unit in a province on the TSR, but it is moved during the movement phase the Russian unit may pass through that territory. CHINA:A KRA-MON, RUSSIAN: A VLA-TSR-MOS. Russian unit gets to Moscow.

2: If a foreign power has a unit in a province on the TSR, but it is moved along the TSR the Russian unit will bump with the foreign power's unit and normal TSR retreat policy will be used. CHINA:A KRA-OMSK, RUSSIAN:A VLA-TSR-MOS. The Russian unit bumps with the Chinese unit in OMSK, the Chinese unit returns back to KRA and the Russian unit returns to IRK.

The OMSK clarification adds another dimension to the use of the TSR. Omsk is the only supply center province not on an end of the TSR. If Omsk is in foreign control but has no enemy unit in it, the Russian unit would have to stop in that province. Of course, the Russian player would not control OMSK until he held it during an adjustment year turn.

The TSR order clarifications show how the movement orders should be written and read to use the TSR in certain situations. The most confusing is when a foreign power is in control of a TSR province and it moves into another province along the TSR. The clarification uses the information in the rulebook and just applies it to the situation.

After much explaining, these symptoms of chaos and confusion were alleviated. This symptom is apparent in all players, but it is dangerously catastrophic to any Russian player who catches it. We hope that this knowledge can help any such person and alleviate the pain and/or discomfort found when contracting CDD.

These notes are from current studies being conducted at the Institute for Higher Diplomatic Involvement. All actual names will be changed and any names used in these notes are not names of actual people. Any similarity is by coincidence and should not be considered slanderous or libel. For more information on CDD, please contact a Doctor at the CDD-Medical Journal.

Tom Pasko publishes CDD Medical Journal, a zine focusing on Colonial Dip.

Why I Love Colonia VII

by Gene Prosnitz

I'm writing this article to urge hobbyists to play Colonia VII, the Diplomacy variant invented by Fred Hyatt. In my opinion, Colonia is the best, and the most interesting, Diplomacy game ever invented.

Its called Colonia VII because there were seven revisions of the map and of the assignment of colonies before reaching the present version, where all nine powers are of approximately equal strength.

To my knowledge, Colonia is the only Diplomacy game where most of the great powers have clusters of centers widely separated from each other, in contrast to regular Diplomacy, where each power starts with a contiguous group of centers. Thus, in Colonia, you may be engaged in four separate wars in four parts of the globe, with different enemies and allies in each sector.

The map is world wide, with 136 supply centers, 47 non-supply center land spaces, and 64 sea spaces. There are 19 island supply centers in the Pacific and Indian Oceans which are totally surrounded by water.

At the start of the game, there are four colonial powers, two semi-colonial powers, and three land mass powers, with starting supply centers as follows:

- England: Two at home, one each in South America, Southeast Asia, and Africa.

- Netherlands: Two at home, one each in North America, Africa, and the Pacific.

- Spain: Two at home, one each in North America, Africa, and the Pacific.

- Portugal: Two at home, one each in North America, South America, and India.

- France: Three at home, one each in North America and Africa.

- Austria: Three at home, one each in South America and the Pacific.

- Russia: Five at home (Europe and Asia), one in Africa.

- Ottoman: Four at home, one in the Pacific.

- China: Four at home, no colonies.

The colonies are surrounded by neutral centers, so that by the end of the second year, a colonial power might have approximately sixteen centers, spread out with four different clusters of four centers each in widely separated areas.

The victory criteria is 50 centers. Most games end in draws, I know of only two games which resulted in a win.

The rules are the same as regular Diplomacy, with one big difference. Any power can build in a colonial home center. For example, England starts off with five centers: London, Liverpool, Nigeria, Malaya, and Ecuador. Only England can build in London and Liverpool. However, an enemy power which captures Nigeria, Ecuador, or Malaya can build there. The colonial home centers are all of the original home centers outside of Europe, except for Omsk, Vladivostok, the Chinese home centers, and the Ottoman home centers.

Here are the reasons why I like Colonia:

- The size of the board makes the game much more complex.

- In Colonia, you need a global strategy. Your decision on why to ally with in Africa will affect developments in America, Europe, and the Pacific. You may have to plan four separate campaigns in different areas.

- The existence of so many separate areas gives you a lot more strategic options and increases the likelihood of a successful survival strategy. In regular Diplomacy, even the best players will be doomed if ganged up on by two or three neighbors. In Colonia, you may be ganged up on in one area, but survive with strength in a different part of the world, where the powers present, and the alliance configurations, are different.

- There are many more permutations and combinations. In a recent game, as Netherlands, at one point I was allied with England and Portugal in North America, and was allied with Russia and Ottoman in Africa. Meanwhile, England and Russia were at war in Europe, and Portugal and Ottoman were at war in Asia.

- Overall strategy, concentrating on the big picture, becomes more important than center grabbing, even when we are talking about neutral centers whose capture won't offend anyone. In regular Diplomacy it would be unheard of to pass up two neutral center builds in the second year. Yet in Colonia, I achieved a powerful positional advantage by doing this in one game. I could afford it because the bypass of the two neutral centers still left me with 13 centers at the end of the second year.

- Colonia has strategic challenges which don't exist in regular Diplomacy, such as how to link up your forces. Isolated colonies can be vulnerable, and you can strengthen your position by linking up two of your colonies. In a recent game, won by Netherlands, the Dutch successfully linked up their forces in Florida and Melbourne, and created a power base stretching across the South Pacific and through Mexico and Central America.

- Related to the above is the strategy of trading colonies. This is difficult to achieve, and rarely seen, and takes a lot of trust, but it can be powerful. In one game (played on the former map), Netherlands started with colonies in Surinam and India, while Ottoman started with a colony in Brazil. The Dutch and Turks traded Brazil for India, the trade taking place at the end of the third year. This had a devastating effect. Netherlands obtained a double colony in South America, and conquered all of South America. Also, the Dutch fleets which left India hooked up with the Dutch forces in Angola to conquer all of southern Africa.

- In regular Diplomacy, most countries' building centers are close together, and the only real tactical choice is whether to build an army or a fleet. In Colonia, you have the question of what part of the world to build in. Sometimes, it is a good strategy to decline to take all of your builds, so that you can build in a key area the next year. In short, you have more complex strategic and tactical options.

- Annihilations are more important in Colonia, since the enemy will often be unable to rebuild in that part of the globe. When fighting a war in the colonial areas, it is usually better strategy to go for the annihilation than to go for a supply center, especially on a spring move.

- Convoys are more important in Colonia than in regular Diplomacy, because they enable you to transfer units to a different sector of the board where there are limited opportunities to build. In a recent game won by Netherlands, the Dutch started their invasion of South America by a surprise build of an army in Melbourne and a convoy to Chile, catching the Portuguese defenders by surprise. (Winter builds and Spring moves were combined in one turn).

- Naval warfare has a greater role in Colonia; as stated earlier, there are 19 island supply centers in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, accessible only by sea. Builds in this part of the world are almost always fleets, the above Melbourne army being a rare exception.

- Stalemate lines are almost non-existent in Colonia. There are a few; for example, two Turkish armies in Baghdad and Armenia can hold off a land invasion from the east, as long as Russia is friendly and as long as the invaders cannot break through by sea into the Arabian Sea and Persian Gulf.

In short, Colonia is a great game. I strongly urge people to try it. And I hope some GMs will run games. I offer to GM a game if someone will publish it.

Machiavelli: A Primer for Diplomacy Players

by Chris Hassler

With Avalon Hill's re-release of Machiavelli last year, a new opportunity has been granted for gamers to experience this gem. Not only is this game back in print after an absence of many years, but its rules have been updated and improved, making it an attractive alternative to Diplomacy. The question then arises, what should a Diplomacy player who has never played Machiavelli look out for? The answer to that question depends on which rules you play with. Machiavelli has a basic game, which closely resembles Diplomacy, and an advanced game, which while still similar to Dip, has some significant departures. In addition to that, there are a number of optional rules which can make things even more interesting. The map is also (obviously) different.

The Map

Machiavelli's map is concerned with Italy. As such, it covers the Italian peninsula and North Italy up to the Alps, Southeastern France, Southwestern Austria, the west coast of the Balkan peninsula, the tip of Tunis, and the islands of Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica. There are also no supply centers per se on the board. There are instead, 44 cities, which in the basic game act identically to supply centers, but which are different in the advanced game. Cities come in three types: unfortified, fortified, and major. There is no difference between the fortified cities and the major cities in the basic game. Certain coastal cities are designated as ports. Fleets may only be built in ports, so just because that city is on the coast, don't think you can build a fleet there. Ports are designated by an anchor symbol next to them.

There are two provinces which have special properties, in kind of the same way that Kiel does on the Dip board. The first of these is Messina. A fleet in Messina controls the Straits of Messina (between Sicily and the toe of the boot) and can prevent opposing fleets from traveling between the Gulf of Naples and the Ionian Sea. An army in Messina, however, cannot prevent such a move. The second special province is Venice. Venice is actually a city in a sea area. As such, armies cannot be built there.

The Basic Game

The basic game of Machiavelli will be very familiar to any experienced Dip player. Diplomacy and order writing work just the same. There are two major differences in the game. The first of these is that there are three seasons each year: Spring, Summer, and Fall. Control of provinces and cities is determined at the beginning of the Spring turn of each year -- functionally the same as in Diplomacy.

The second difference is the fact that there is a third type of unit other than armies and fleets: garrisons. Garrisons can exist in any fortified city (which is most cities). They only have available to them three different types of orders: hold, support, and convert, and their support is limited to units in the same province. However, such support cannot be cut, so garrisons can provide a strong defensive benefit. Garrisons can convert into either a fleet (if in a port) or an army. Armies and fleets in port can also convert into garrisons, which allows players to shift their military assets from land to sea (albeit slowly, since it takes two turns to convert a fleet to an army or vice versa). How can you get rid of that pesky garrison? By siege, of course. Any army or fleet (if the city is a port) can be ordered to besiege an opposing garrison. The first turn of the siege, the garrison unit is placed on top of the besieging unit. While besieged, any convert order issued by the garrison automatically fails. If the garrison is successfully besieged a second turn, it is eliminated. In all scenarios, certain neutral cities start the game occupied by autonomous garrisons. These garrisons serve only to make it more difficult to gain control of the provinces in question.

The Advanced Game

The advanced game is where Machiavelli starts to diverge from Diplomacy in a major way. The advanced game introduces an economic element into the game. No longer is your ability to support units dependent on the number of cities you occupy. Instead, you receive a number of ducats each spring, during the Income and Military Unit Adjustment Phase. With these ducats, you can build and maintain your units as well as engage in more devious activities.

Income comes from four different sources. For each province you occupy or control, you receive one ducat. For each sea area you occupy, you also receive one ducat. Fortified and unfortified cities are also worth one ducat apiece. Major cities are worth either two ducats each (Rome, Naples, and Tunis) or three ducats (Venice, Milan, Florence, and Genoa). If a city is besieged, however, it produces no income. Finally, each country receives variable income. A single die is rolled and all countries cross-index that number on a chart which determines a base number from one to six, depending on the country. In some scenarios, certain countries actually double the amount of variable income received. Ducats can also be saved from turn to turn, and can be traded or loaned to other players. Such loans, however, are not enforceable....

Now that you have collected your income for the turn, the question then becomes, what to do with it. The first obvious answer is to build and maintain military units. All military units cost three ducats to build or maintain. You can disband units at this time by simply not maintaining them. You can even build new units instead of maintaining existing ones -- and those new units need not be of the same type as the original, except that the new unit cannot be built in the same province the old unit occupied. Units must be built in home nation cities, and only one unit may be built in each city per year.

Another use for ducats is bribery. By spending a sufficient number of ducats, you can eliminate an opponent's unit, or even convert it into one of your own. The owning player can attempt to block you by counter-bribing the unit, however. To the amount of the counter-bribe is subtracted from the amount spent on the bribe, and if the bribe is above a certain threshold (which depends on the type of bribe attempted), the bribe succeeds. Regardless of the success or failure of the bribe, all ducats spent on the bribe and counter-bribe are lost. Counter-bribing must be in increments of three ducats. To disband an enemy unit, at least 12 ducats must be spent. To buy one, 18 ducats is required. Garrisons can be converted to autonomous garrisons for 9 ducats. Autonomous garrisons can be disbanded for 6 ducats or bought for 9 ducats. The costs of the last three activities are doubled if the garrison is in a major city. Since expenditures take place before regular unit movement, you can issue orders to newly converted units. For example, if Milan were to buy a French army, it could also write orders for that army for the same turn.

The Optional Rules

The game also comes with a number of optional rules which add even more chaos to the mix. These rules can be used in any combination, but many of them only make sense with the advanced game.

- Excommunication: The player playing the Pope can excommunicate any other player (or in the case of the Turk, declare a crusade). This has the effect of barring that player from conducting diplomacy with any other player who is not likewise excommunicated. If any non-excommunicated player does conduct diplomacy with the excommunicated player, he also becomes excommunicated. This can backfire on the Pope, since if all other players are excommunicated, the Pope cannot conduct diplomacy at all, since he can't ever be excommunicated. Excommunication only lasts one turn.

- Natural Disasters: There are two natural disasters which historically afflicted Italy during this period: Famine and Plague. Famine is determined at the beginning of the spring turn. A die is rolled to determine how bad the famine is. The results can either be no famine, a single roll on either a row or column of the famine table, or a roll on both a row and column of the table. Any province stricken by famine produces no income (except for a garrisoned city), units may not be built there, and units remaining there at the end of the spring turn are eliminated. Famine can be relieved by the expenditure of three ducats. While this does not remove the first two effects of famine, it does make it safe to stay in the province. Plague occurs at the beginning of the summer turn of each year.

- Special Units: Military units during this period were primarily condottieri, or mercenaries. A number of different types of units were experimented with during this period, and this optional rule allows players to use those units. Each player is limited to a single special unit in play at any one time, regardless of the type. The types of special units are: Citizen Militia, Elite Mercenaries, and Elite Professionals.

- Strategic Movement: This option allows each player to move one or two units any distance through controlled areas.

- Money Lenders: Need a few ducats for that all-important bribe? Well, just go to your friendly neighborhood usurer. You can borrow up to 25 ducats for one or two years.

- Conquest: With this option, players are eliminated as soon as they no longer control any of their home nation cities. It also allows other players to conquer countries.

Conclusion

Machiavelli is a game which is similar enough to Diplomacy that Dip players won't feel too much out of place, but which opens the door up to many new and different kinds of treachery and deceit, both things dear to the heart of any successful Dip player. At the expense of a little additional complexity, Machiavelli has a richness that goes beyond plain Diplomacy. While the randomness of certain aspects of the game may not appeal to the Dip purist, it results in situations which are always in motion, rarely ending in a stalemate or draw. Machiavelli is definitely the type of game which encourages the solo victory, and how many of you would prefer to share a victory when you can have it by yourself? Enough said.

A Call to Arms Against Crap Variants

by Stephen Agar

As someone who has always been a big fan of variants, in my day I've run a variant-only zine and designed more variants than I've had hot dinners, well, more than I've had Thai hot dinners, I have no hesitation in saying that most variants are crap. And what's more, thanks to the Internet, crap variants are coming back into fashion (though, like the IRA, they never went away, you know). There are many different types of crap variants, but the ones I dislike the most are those which only make a small change to one of the basic Diplomacy rules, so that the game is 98% a regular game. If all you're going to do is to make a single rule change then, unless the rule change is fundamental and significantly alters the way the game is played, why bother?

This is what has happened on the Internet - lots of American students are thinking up minor rule changes all the time and launching their new" variants on the world. What's worse, due to the scarcity of high-quality variants available on the Internet, some of these games are actually being played. The difficulty in transferring graphical images through the Internet without a resource such as a large Web page or a FTP site, and the fact that most maps already available are in postscript format (when few home users have postscript printers) means these minor rule change variants flourish. Hell, they have even invented numerous versions of Gunboat, which is probably the most inane variant ever invented, and write articles on what it really means when another Gunboat power supports your unit to Switzerland?!? Gunboat... how I hate Gunboat...